Our foraging in Tulear is an education, especially for Lance who is less familiar with African towns, and finds it fascinating. Tulear is a bustling, busy town. Like many similar places in Africa, the infrastructure is run down and dilapidated, pavements and roads are cracked and potholed, and there are piles of litter everywhere. Shanties and roadside stalls are interspersed with brick buildings whose painted exteriors are peeling and cracked, but the streets are teeming with people going about their affairs.

People get around either by walking or by catching apousse-‐pousse

(push-‐push) – a kind of rickshaw with a roof – and they are everywhere – lining the roads waiting for a fare or shooting through intersections. There are tricycles too. Each is typically laden with 2-‐3 passengers in bright clothes, their shopping and the occasional chicken. The average fare is around 2000Ariari – about

R8. The streets are potholed and teeming withpousse-‐pousse, people, a few trucks and vehicles and zebu carts. Chickens dart in between vehicles, and shacks and stalls encroach onto the roadway.

There are street-‐side vendors selling fresh produce every few metres – each with a different speciality – oranges, lettuce, tomatoes, baguettes, fizzy drinks. Some have cooked or baked items for an early breakfast. Conventional shops, with their set back entrances, offer the promise of cool darkened interiors with consumer goods of every description piled in seeming disarray.

Jose knows his way around and takes us promptly to the places we need to go. First, Lance needs to get to Air Madagascar. He is all packed and ready and his baggage loaded into Jose’s taxi. We drop him at the Air Madagascar offices to change his flight – he discovers that the airline has no record of his booking anyway. He manages to get on a later flight to Antananarivo and will have to overnight there. We hear later that his flight is cancelled, and he spends an extra night in Tulear in a hotel. We wonder which one!

The rest of us go out to change money. When we return, Lance has sorted out his ticket and we find him sitting on the pavement outside Air Madagascar, rucsac on his lap, looking at the passing street life with delight on his face.

After dropping Lance at Zanzibar restaurant, which has wifi, we split up. We need to buy 600l of diesel, which can only be done by taking 25l

containers to the local garage, then transporting them back to the boat and decanting. This needs to be done several times and is Paul’s job. Jose’s car suspension battles to cope with the combined weight of people and fuel on the potholed roads and the vehicle grinds painfully every time it goes over a bump or dives into a pothole.

Steve and Gibby head to the market. Not wanting to take a chance with the open-‐air meat market, and its innovatively butchered fresh cuts of meat laid out in the morning sun, we opt for fresh produce only. Gibby promptly abandons Steve to the badgering of the market vendors and disappears to the hardware store. There is a lot of fresh produce, but of varying quality, and there are dozens of vendors in the shaded market selling similar wares, so the competition is fierce. Everything is sold and priced in kilos – and produce is weighed on old-‐fashioned balance scales. The weights used to measure are interesting, to say the least. A combination of a 500g steel weight, a few shampoo bottles full of water, and a stone equate to a kilo it seems.

The pressure to purchase is huge as each person is very keen to make a sale, and one has to be careful not to end up with multiple kilos of the desired item. Un kilo quickly becomes Deux or Trois kilos if one is not paying

attention. Fruit is cut open to sample, andSteve is invited to prod, taste, squeeze, heft or otherwise experience items in the hope of securing a sale. As soon as he indicates interest in an item, 5 or 6 examples of that item are thrust into his face by different vendors, and even when the desired kilo is bought, there is pressure to buy more of the same for the next 20 minutes. There is a big oversupply of small limes and lemons. The main way of trying these is to cut them in half, and then squeeze the juice onto the hand. Sometimes they do this to you while you are not looking. Things get sticky.

Compromise and adaption are needed here– it’s not like going to a supermarket back home. Fruit is often small and spotty and is usually unripe – giving it a longer shelf life in the heat. The potatoes and ginger are small and still covered in the brown earth but still seem good, and the problem of how to transport 2 dozen eggs is swiftly solved when a small cardboard box is procured, and the eggs laid carefully onto layers of straw.The prices are scribbled onto bits of cardboard or paper and added up at the end.

Steve secures tomatoes, courgettes, beans, lettuce, mangoes, oranges, pineapples, bananas, and even a few exotic items like ginger (of course!) and fresh basil. Exhausted, sticky from the impromptu tastings, and somewhat frazzled, he concludes the trade (around R160 worth). We will have enough produce for a week or so, especially if we rinse it all in Milton and store it in the fridge. He arranges with the vendor to hold the stuff for later collection and escapes into the bright sunlight of the street.

Paul has meanwhile parted with around Ar 1,8 million for diesel and the fuel tank on the boat is now full. We have enough diesel to get to Nosy Beif we have to. Gibby has secured his plumbing and electrical goods and so we repair to Zanzibar restaurant to recover from the heat and dust. Ice-‐cold Three Horse beer and some lunch go down well, and a woman selling semi-‐precious stones entices Gibby to examine her wares. He buys a beautiful clear blue topaz and a pair of sapphires as a gift for his beloved, and oft-‐mentioned Michelle.

After a final trip to the airport to drop a happy Lance off, we are ready to leave. Paul has been doing the running around with all the port officials (after our experience in Durban, he is good at this!) and he returns looking irritated: he has had to part with ‘un petit cadeau’ -‐ a little ‘present’ -‐ for each official of between R50 and R150 a time. These little presents have amounted to over R1000 in one morning. What a rip-off, Madagascar style! We are told later by Catherine at Safari Vezo that we got away lightly.

It is hot, we have had enough of officials and paperwork, and are feeling a little bruised and much poorer from the haemorrhaging of money. We are also feeling a little uncomfortable about the people hanging around the boat at the port. Paul finally manages to get the port clearance document when the port captain returns from his leisurely lunch/siesta at 4 pm. It is time to get out of Tulear. But not without paying more money to Jose (R600) and the guardian for their work.

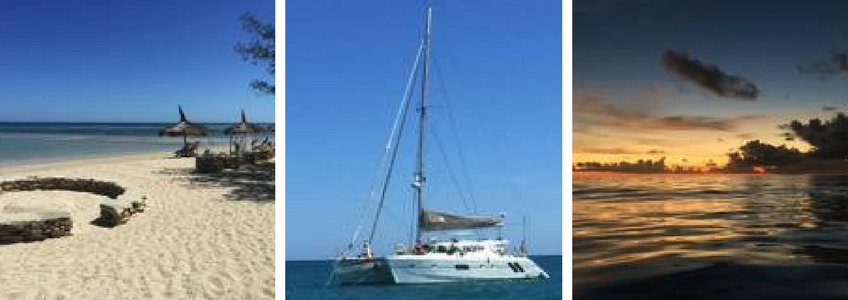

We escape from Tulear – three men in a boat. We are not going to make it to all the way to Anakaoin daylight and the sea is bumpy with the afternoon onshore breeze. But there is a beautiful line of cliffs ahead of us glowing red and warm in the setting sun, and Gibby recalls anchoring in the lee of the cliffs previously.

We ease in under the cliffs where there is calm water and drop anchor. What a beautiful spot; the charts say it is called Salary. There is an estuary and a deep gorge so the river must be ancient. A long sandy spit curves out from the one bank, and behind it nestles a fishing village– we can see small figures moving along the beach and the lines of pirogues dragged up for the night. A strong tidal rip makes silver and indigo stripes on the water and Catch My Drift swings on the anchor bridle.

Another beautiful evening; a beautiful sunset, some cold beers on the trampoline and the peace and quiet of being away from it all. The talk is muted; we all wish our family and friends could be there to share this moment.